AlphaSimR is a package for performing stochastic simulations of plant and animal breeding programs. It is the successor to the AlphaSim software for breeding program simulation (Faux et al. 2016). AlphaSimR combines the features of its predecessor with the R software environment to create a flexible and easy-to-use software environment capable of simulating very complex plant and animal breeding programs.

There is no single way to construct a simulation in AlphaSimR. This is an intentional design aspect of AlphaSimR, because it frees users from the constraints of predefined simulation structures. However, most simulations follow a general structure consisting of four steps:

- Creating Founder Haplotypes

- Setting Simulation Parameters

- Modeling the Breeding Program

- Examining the Results

The easiest way to learn how to use AlphaSimR is to learn about these steps. The easiest way to learn about these steps is to look at an example, so this vignette will introduce AlphaSimR by working through a small example simulation. The example will begin with a description of the breeding program being simulated. This will be followed by sections for each of the above steps and conclude with the full code for the example simulation.

Example Breeding Program

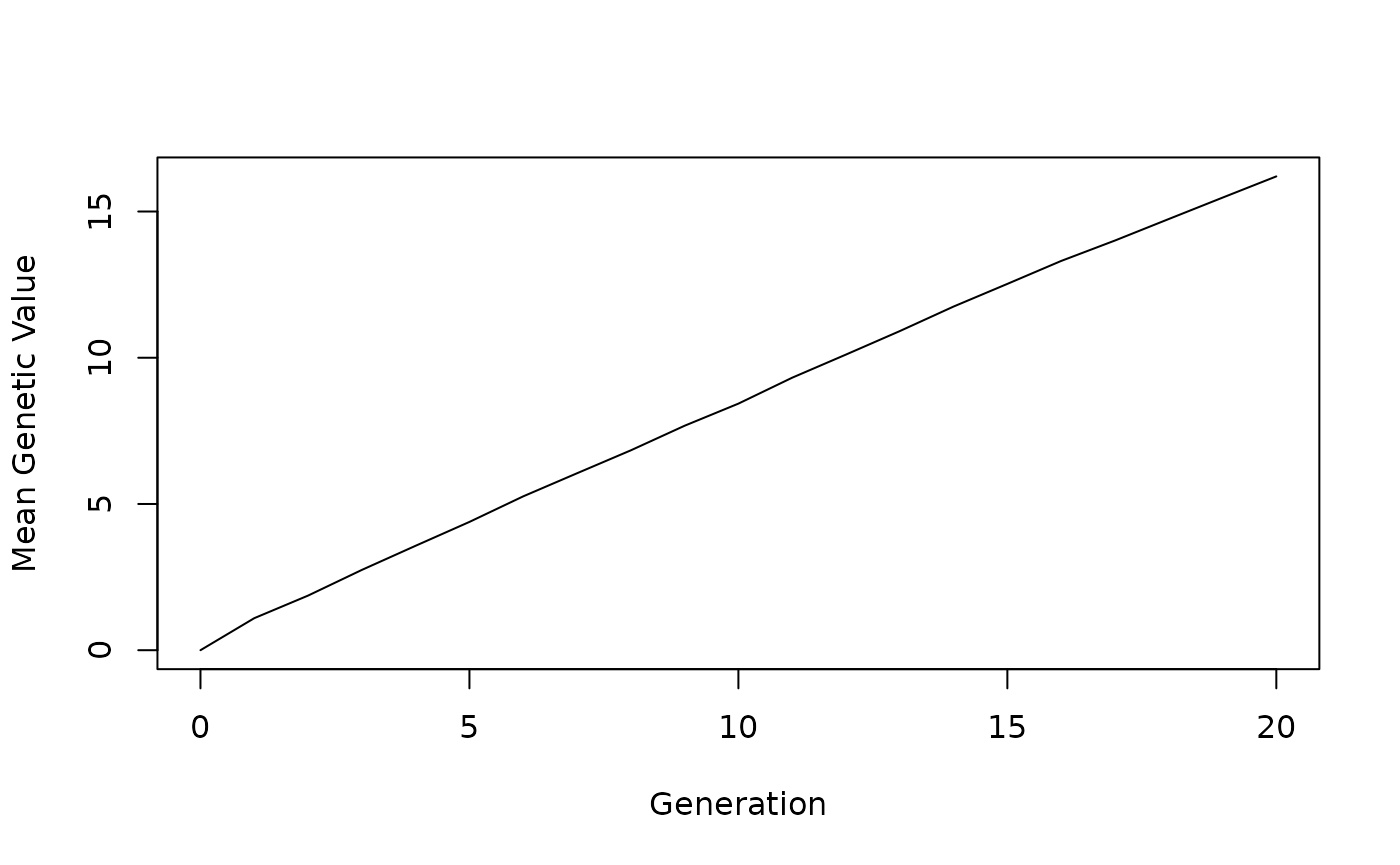

A simplified animal breeding program modeling 20 discrete generations of selection. Each generation consists of 1000 animals, of which 500 are male and 500 are female. In each generation, the best 25 males are selected on the basis of their genetic value for a single polygenic trait and mated to the females to produce 1000 replacement animals. The quantitative trait under selection is modeled as being controlled by 10,000 QTL. These QTL are equally split across 10 chromosome groups so that there are 1,000 QTL per chromosome. The mean genetic value of all individuals in a generation is recorded to construct a plot for the genetic gain per generation.

Creating Founder Haplotypes

The first step in the simulation is creating a set of founder haplotypes. The founder haplotypes are used to form the genome and genotypes of animals in the first generation. The genotypes of their descendants are then derived from these haplotypes using simulated mating and genetic recombination. For this simulation, only a single line of code is needed to create the haplotypes, and it is given below.

founderPop = quickHaplo(nInd=1000, nChr=10, segSites=1000)The code above uses the quickHaplo function to generate

the initial haplotypes. The quickHaplo function generates

haplotypes by randomly sampling 1s and 0s. This approach is equivalent

to modeling a population in linkage and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium with

allele frequencies of 0.5. This approach is very rapid but does not

generate realistic haplotypes. This makes the approach great for

prototyping code, but ill-suited for some types of simulations.

The preferred choice for simulating realistic haplotypes is to use

the runMacs function. The runMacs function is

a wrapper for the MaCS software, a coalescent simulation program

included within the distribution of AlphaSimR (Chen, Marjoram, and Wall 2009). The MaCS

software is used by AlphaSimR to simulate bi-allelic genome sequences

according to a population demographic history. The runMacs

function allows the user to specify one of several predefined population

histories or supply their own population history. A list of currently

available population histories can be found in the runMacs

help document.

An alternative choice for providing realistic initial haplotypes is

to import them with the newMapPop function. This function

allows the user to import their own haplotypes that can be generated in

another software package or taken directly from real marker data.

Setting Simulation Parameters

The second step is setting global parameters for the simulation. This can be done with three lines of code. The first line initializes an object containing the simulation parameters. The object must be initialized with the founder haplotypes created in the previous step and the code for doing so is given below.

SP = SimParam$new(founderPop)The output from this function is an object of class

SimParam and it is saved with the name SP. The

name SP should almost always be used, because many

AlphaSimR functions use an argument called “simParam” with a default

value of NULL. If you leave this value as

NULL, those functions will search your global environment

for an object called SP and use it as the function’s

argument. This means that if you use SP, you won’t need to

specify a value for the “simParam” argument.

The next line of code defines the quantitative trait used for selection. As mentioned in the previous section, this trait is controlled by 1000 QTL per chromosome. The rest of the function arguments are left as their defaults, which include a trait mean of zero and a variance of one unit.

SP$addTraitA(nQtlPerChr=1000)The ‘A’ at the end of SP$addTraitA indicates that the

trait’s QTL only have additive effects. All traits in AlphaSimR will

include additive effects. Traits may also include any combination of

three additional types of effects: dominance (“D”), epistasis (“E”), and

genotype-by-environment (“G”). A specific combination of trait effects

is requested by using a function with the appropriate letter ending. For

example, a trait with additive and epistasis effects can be requested

using SP$addTraitAE. The following trait types are

currently offered: “A”, “AD”, “AE”, “AG”, “ADE”, “ADG”, “AEG”, and

“ADEG”.

The final line of code defines how sexes are determined in the simulation. Sex will be systematically assigned (i.e. male, female, male, …). Systematic assignment is used to ensure that there is always equal numbers of males and females.

SP$setSexes("yes_sys")Modeling the Breeding Program

We are now ready to start modeling the breeding program. To begin, we

need to generate the initial population of animals. This step will take

the haplotypes in founderPop and the information in

SP to create an object of Pop-class.

pop = newPop(founderPop)A Pop-class object represents a population of

individuals. A population is the most important units in AlphaSimR,

because most AlphaSimR functions use one or more populations as an

argument. In this regard, AlphaSimR can be thought of as modeling

discrete populations as its basic unit. This contrasts with its

predecessor, which used discrete generations.

Populations are not a fixed unit in AlphaSimR. Many functions in

AlphaSimR take a population as an argument, modify the population, and

then return the modified population. Populations can also be used

“directly”. For example, you can pull individuals out to form new

(sub-)populations using [] and you can merge populations

together using c(). This functionality is particularly

useful for performing tasks in AlphaSimR that lacks a built-in function.

However, the example breeding program presented here is easily modeled

using built-in functions.

Before continuing to model the breeding program, you should first think about the data you’ll need for examining the results in the next stage. This is because you must expressly request that the relevant data is saved. AlphaSimR is designed this way for increased speed and reduced memory usage.

In this example a plot of the generation mean over time is desired. All that is needed to construct this plot is a vector containing the mean in each generation. To start this vector, the mean in the current generation is saved as “genMean”. In each subsequent generation, the mean of that generation will be added to “genMean”. Measuring the mean in the current generation is accomplished with the code below.

genMean = meanG(pop)The final lines of code are for modeling 20 generations of selection

and mating. AlphaSimR has a host of functions for modeling both

selection and mating. In this example the selectCross

function is used, because it efficiently combines both selection and

mating in a single function call. The function itself actually uses two

separate function in AlphaSimR, selectInd and

randCross for selection and mating, respectively.

To model multiple generations of selection, the function call is

placed within a loop with a line of code for tracking the population

mean. Using a loop makes code easier to read and avoids needless

duplication. In this loop “pop” is overwritten in each generation. Doing

this keeps memory usage low and keeps the code simple. However, if the

user needed to retain older populations there are several alternative

approaches that could be adopted. These approaches include giving each

population a unique name, storing populations as elements in a list, or

dynamically growing populations with c(). The code for the

loop is given below.

for(generation in 1:20){

pop = selectCross(pop=pop, nFemale=500, nMale=25, use="gv", nCrosses=1000)

genMean = c(genMean, meanG(pop))

}Examining the Results

The last step to a simulation is examining the results. In this example there is only one result: a vector of population means for each generation. To examine this result, the code below will produce a basic line plot.

plot(0:20, genMean, xlab="Generation", ylab="Mean Genetic Value", type="l")Full Code

# Creating Founder Haplotypes

founderPop = quickHaplo(nInd=1000, nChr=10, segSites=1000)

# Setting Simulation Parameters

SP = SimParam$new(founderPop)

SP$addTraitA(nQtlPerChr=1000)

SP$setSexes("yes_sys")

# Modeling the Breeding Program

pop = newPop(founderPop)

genMean = meanG(pop)

for(generation in 1:20){

pop = selectCross(pop=pop, nFemale=500, nMale=25, use="gv", nCrosses=1000)

genMean = c(genMean, meanG(pop))

}

# Examining the Results

plot(0:20, genMean, xlab="Generation", ylab="Mean Genetic Value", type="l")